Can we Build Our Way to Affordable Housing?

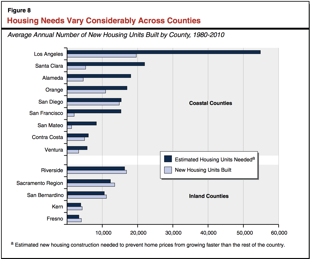

Of the coastal counties, San Diego is the only one that has come close to fulfilling its housing need. Inland counties are fully meeting their housing needs. "California’s High Housing Costs, Causes and Consequences" Legislative Analysts Office

A recent article in the Washington Post speaks to California’s affordable housing problem which it blames on California’s regulatory policies that have limited housing availability. The solution, clearly, is remove all barriers and regulations to building and the problem will be resolved. Affordable housing for all. But, will simply building more housing bring prices down in a material way? I don’t think there’s any doubt that more housing is needed, but the question is how and where to put it, and, importantly, will it affect the cost of housing.

How many units would we need to make housing affordable in California?

I revisited a report from the non-partisan Legislative Analysts Office I had studied a few years back. It states that, from a purely supply standpoint, in order to keep our housing prices similar to the rest of the country, we would have had to have built many, many more units (about 90,000 more per year) over the past 30 years. That amounts to an additional 2.7 million households would have been needed just to keep up with the demand. Moving forward, we’d have to build that many houses per year just to catch up.

Suburban sprawl has not lowered housing costs.

The LAO makes an important point that these houses would have had to have been built closer to the coastal and urban areas (where the demand is); instead we built way too much in the outlying areas (outside the 25 mile radius from the urban cores). In other words, we built out instead of up. The LAO analysis states that the demand, in effect, is driven by the coastal and urban zones not the outlying areas, so building in the outlying areas does nothing to meet this demand. Basically, while we built housing in our urban areas at about the same rate as other metropolitan areas, we built suburban housing at a much higher rate than almost anywhere else in the country. According to the LAO, we should have done the opposite.

Where is this demand coming from?

Well, LAO analysis does not focus on where the demand comes from. It simply analyzes what it would take for our housing costs to be closer to the national average, not really who would live in those houses. Natural population growth (births vs. deaths) and current immigration growth would not be enough to fill the three million or so extra houses required to bring costs down, so that demand is from people coming in from out of state and from those who choose to stay put rather than leave. Why do they come?

Amenities drive the demand for living in a given place. In economic parlance, amenities refers to the attributes of a region that make it desirable to live there: economic amenities (jobs), cultural amenities (restaurants, shopping, museums, nightlife) and importantly, for those of us living in San Diego, natural amenities (good weather, open space, fresh air, beaches, mountains, recreation).

It is this desirability–amenities in other words–combined with the limited supply of housing that drives up the price. The amenities that San Diego offers attract people from all over the country (and the world). There are always more people willing to move here and willing to pay the premium to live here than there are houses able to accommodate them. This is how a free market works.

All of California’s coastal regions are amenity rich. As Jerry Nickelsburg, respected economist and director of UCLA's prestigious Anderson Forecast, puts it:

_________

_________

The downside of affordability:

To lower prices to a significant degree would require increasing our housing significantly and thusly increase our population with all the problems that would inevitably bring. If we had built “enough” housing, our population would be much greater (according to LAO: about 7 million more people than we have today, and in SF, double the population). We have to ask if that would have been a good outcome or not. Our cities would, at the very least need to get a lot taller and perhaps we would have to put more emphasis on transit. But we wouldn’t be really addressing the significant consequences of a much greater population. Question is, is the solution to the affordable housing worse than the problem itself? That is something we need to analyze carefully.

What about the teachers and firefighters?

What about the teachers and firefighters and the other folks a city depends on to function properly? Well, that is a conundrum. They either have to commute long distances (not ideal) or squeeze themselves into increasingly tighter quarters. Or perhaps, we could pay them more, though some might argue that this would likely increase the tax burden and not politically tenable. Nickelsburg believes that market-based solutions will never make housing truly affordable because there is simply too much interest in living in places like San Diego. And forcing developers to build affordable housing would likely not work because, frankly, the price of housing is not really up to them. In a tight market, the price is not dictated by the seller, but by the competing interests of buyers seeking limited housing. One potential solution Nickelsburg suggests is exemplified by a program in Santa Clara County that builds high quality housing that it rents to teachers. That could be an interesting approach and probably worth researching more.

What about San Diego specifically?

The LAO report focuses on California as a whole, but there are a few call outs regarding San Diego. Compared to the national averages, San Diego is very expensive. However, when compared with all of California, San Diego average rent and home prices are just slightly above the average. At the low end are inland counties with cities such as Fresno and Bakersfield who are closer to the US average. At the high end, the Bay Area with median home prices in San Francisco being about 100% higher than in San Diego and rents about 50% higher. It also shows that over the past 30 years, most coastal urban areas in California have delivered significantly fewer houses than would have been needed to prevent housing costs from rising. As expected, inland Counties have generally met or exceeded their housing needs while the coastal regions have not. And, of the coastal counties, San Diego is the only one that has come close to meeting its demand, though the need is still higher than the supply. This suggests that the narrative focusing on California’s housing crisis, while applicable to San Diego, paints a less dire picture than the rest of coastal California (Figure 8).

Is the cost of building a home driving up the cost of housing?

The LAO’s analysis suggests it does not. In a highly desirable area like San Diego, the building costs (construction materials, regulations) have little impact on the overall price of a home because the price of a home is driven up by the high demand to live here, not by the cost of building. In areas that have fewer amenities (say Cleveland) the demand is lower and the cost of building a home does impact the price of housing because competition drives the purchase price closer to the actual builder’s costs. From the same LAO study:

Incidentally, all of this contradicts the highly suspect claim put forth by the Building Industry Association (through a study they commissioned by a local college, Point Loma Nazarene University) that 40% of housing costs are due to regulation. It should be noted that the data used to generate that research was entirely provided by builders themselves, including the data that could have been obtained directly from the source (permits, regulatory fees, etc.).

In Summary:

Links

“In general, because unmet demand results in competition for housing and rising costs, home prices and rents are highest where unmet demand is greatest. These price trends, therefore, suggest that unmet demand for housing is greater in central cities relative to surrounding areas. More housing development was needed in central cities relative to surrounding areas to contain growth in housing costs.” (California’s High Housing Costs, Causes and Consequences) P.22

“Natural amenities are valuable. People like to live in physically beautiful areas and in areas with mild weather and an abundance of outdoor activities. Consequently, the amenity index should predict a higher level of demand due to this household preference and consequently a higher price for housing.” (Pricing the Natural Environment: How Amenities Put a Premium on California Housing)

“The market increases prices to ration the available land through the cost of housing. And people economize on their consumption of housing by living in smaller quarters, sharing with roommates, or stacking up generations. And for some, the price is not worth the value they would receive, and they leave. That is how any market rationalizes differences between supply and demand." (Why the Housing Crisis won't get Fixed by Building Cheaper Homes, Nickelsburg)

The cities that we find most attractive are cities where housing is “unaffordable.” In other words, the affordable housing crisis is not just about a lack of housing supply.

“Building costs account for around one-third of home prices in California’s coastal metros. Under these circumstances, as Figure 6A shows, building costs explain only a small portion of growth in housing costs. Instead, increasing competition for limited housing is the primary driver of housing cost growth in coastal California. (California’s High Housing Costs, Causes and Consequences). p.14

Copyright 2018, Grow the San Diego Way